January 21, 2014

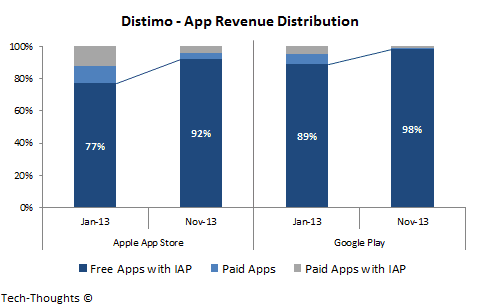

According to Distimo’s latest report, apps with “freemium” business models, i.e. free apps monetized by in-app purchases (IAP), have dominated revenue charts in 2013. This spurred me to take a deeper look at the “economics of free” and explore new opportunities for innovation in these business models.

The Economics of Free

Let’s begin by taking a brief look at the “Economics of Free” or the “Economics of Abundance”, as described by Mike Masnick. Here’s a short, 2 minute video introducing the concept:

Economics is essentially a social science that examines the best possible way to allocate “scarce” goods or resources, i.e. ones with meaningful marginal cost and limited supply. However, digital goods like apps are abundant because the marginal cost of creating an additional copy is zero. Given the nature of near-efficient competition in the digital world, price naturally approaches the marginal cost of zero.

This explains the decline in popularity of paid app downloads and the decline of numerous traditional business models. However, cheap or free content allows developers to reach a much wider audience which consequently increases demand for related scarce goods or resources. In the music industry, the advent of digital music precipitated a steep decline in US recorded music sales from $14.6 billion in 1999 to just $6.3 billion in 2009, but concert ticket sales grew from $1.5 billion to $4.6 billion over the same timeframe. In other words, digital music converted a scarce resource (recorded music albums) into an abundant resource (cheap, easily downloadable singles), which then increased demand for a related scarce resource, i.e. concert tickets.

- Marginal Cost – Cost of producing an additional unit

- Efficient Competition – Participants do not have the market power to set prices

The Pyramid of Scarcities

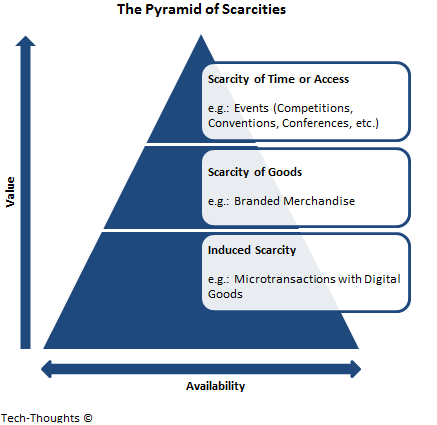

This particular study focuses on scarcity-driven monetization opportunities available to developers of free-to-play (F2P) games like Candy Crush Saga, Angry Birds, etc. As shown in the image below, the scarcities created by F2P games can be segregated into 3 categories, in order of increasing scarcity (or decreasing availability)

- Induced Scarcity

- Scarcity of Goods

- Scarcity of Time or Access

1. Induced Scarcity

Induced scarcity is one that does not exist in reality, but is created artificially — for example, in-app purchases of digital goods. The availability of these goods isn’t really in question and therefore, the value placed on each purchase or transaction is quite low. Consequently, effective monetization depends on maximizing transaction volume from these low-value digital goods, i.e. micro transactions. This strategy is most effective when scarcity is induced because of direct player engagement, and not when it is forced onto players. Game design plays a critical role here as in-app purchases need to be naturally blended into gameplay elements. King’s games like Candy Crush Saga are perfect examples as players pay for boosters to help them progress through difficult levels. In fact, King’s revenue is expected to top $1 billion this year, almost exclusively driven by micro transactions on Facebook and mobile games.

However, exclusive use of this monetization strategy also brings up some challenges. King’s “Games Guru”, Tommy Palm, recently said that 70% of the players on Candy Crush Saga’s final level “haven’t paid anything”. While this is a great sign for consumers, King seems to be losing out on monetizing their most engaged players and biggest fans (excluding a minority population of “whales”). The only reason these players haven’t become paying customers is because they don’t consider digital goods to be scarce enough. The solution isn’t to create “paywall” equivalents, but to explore additional monetization opportunities with even scarcer products.

2. Scarcity of Goods

Scarcity of goods refers to physical products that have a tie-in with an F2P game — for example, branded or licensed merchandise. Since physical goods aren’t as abundant as digital ones, the value placed on each transaction is automatically higher. However, this comes with the trade-off of lower transaction volume. Rovio’s Angry Birds franchise is a great example of a successful merchandising strategy. Led by sales of Angry Birds plush toys, merchandising and IP sales made up 45% of Rovio’s $195 million revenue in 2012. This year, Hasbro sold over one million “Telepod” figures within a month of Angry Birds Star Wars II’s launch. This year, King also dipped its toe into merchandising with a range of Candy Crush themed candies and socks.

These products are likely to appeal to fans of F2P games even if they have never purchased digital goods. However, the biggest fans and most engaged players may be looking for something even scarcer.

3. Scarcity of Time or Access

Scarcity of time or access can be leveraged through a direct connection with the most ardent fans — for example, events like gaming competitions or conventions. Conventions tap into scarcity of time from key personnel like game designers, while social gaming competitions tap into scarcity of access to exclusive benefits and direct competition with other “superfans”. The monetization opportunity from events is likely to be immense, even though the actual frequency may be low.

So far, very few game developers have utilized this particular strategy — a related example from the non-F2P space is Mojang’s Minecraft Convention or MineCon. 7,500 tickets to the event sold out in roughly 5 minutes, generating roughly $1 million in revenue. This may seem like small change for large gaming companies, but it’s important to keep in mind that Mojang may view MineCon as more of a promotional event. Expanded ticket sales and advertising partnerships could easily make gaming events a significant revenue opportunity. Given the competition in allied industries like mobile hardware, there will certainly be no dearth of advertisers.

Opportunity for Innovation

The monetization opportunities outlined in this post show that the free-to-play mobile gaming industry still has a lot of room for growth. Most publishers have focused on just one of these strategies and I have no doubt that we will see more business model innovation from these companies as we move forward.

Having said this, these strategies are only useful for companies if their games remain popular. The gaming industry has proved again and again that companies cannot rest on the laurels of a single mega-hit. Therefore, developers need to focus on continuous innovation across a wide catalog of games. What’s most important is to ensure that players have fun. After all, isn’t that the entire point of playing games?

– Sameer

This post was originally posted in Sameer’s Tech-Thoughts blog – you can find the original article here.

Sameer is a business strategy professional with expertise in mobile ecosystems, asymmetric business models and disruptive innovation. Over the last 6 years, he has held various roles in strategy consulting, investment management, M&A and venture capital. During this time, he has developed a keen interest in the intersection between technology, innovation and business strategy. You can follow his work on his blog at Tech-Thoughts, on Twitter @sameer_singh17 or on LinkedIn.

Recent Posts

August 27, 2025

How to Find the Right Learning Path When You’re Switching to a Tech Career

See post

August 27, 2025

The Hidden Challenges in Software Development Projects: Key Insights from Our Latest Survey

See post

August 22, 2025

Developer News This Week: AI Speed Trap, GitHub Copilot Agents, iOS 26 Beta Updates & More (Aug 22, 2025)

See post